The Logistic Map: From Simplicity to Chaos

Complexity can Emerge from Simplicity

Introduction

How can a formula so simple hide a universe of complexity? This question has often drawn me to the logistic map, a humble recursive equation that captures the full drama of chaos theory. Imagine a rule, almost childlike in its structure, that can predict whether a population of rabbits will settle peacefully, oscillate rhythmically, or spiral into utter unpredictability. What begins as a modest attempt to describe population growth soon transforms into something far richer—a window into the unpredictability of nature, the hidden symmetries of mathematics, and the intricate geometries of fractals.

For me, the logistic map is not just a mathematical curiosity—it is a bridge. On one side lies the classical mathematics of growth, shaped by thinkers like Malthus and Verhulst, who sought to capture the balance of life and resources. On the other lies the modern computational era, where the logistic map reveals cascades of bifurcations, chaotic attractors, and deep ties with the fractal universe of Julia sets and the Mandelbrot set. This is the true magic of the logistic map: it shows us how determinism and unpredictability can coexist, how a line of algebra can blossom into infinite self-similar structures, and how the same mathematics that governs populations can also illuminate the shared DNA of chaos and fractals.

From Malthus to May: A Historical Journey

In the late 18th century, Thomas Malthus described how populations grow exponentially, doubling unchecked if resources are unlimited. This was inspiring but unrealistic—resources are never infinite. In 1838, Pierre François Verhulst refined this with the logistic equation:

Here

What happens if we treat the logistic process in discrete steps rather than continuous time?

His answer fundamentally reshaped how scientists perceive determinism and unpredictability, planting one of the most fertile seeds that would later blossom into the rich and complex field of chaos theory.

The Logistic Map: Where Simplicity Meets Complexity

Logistic Map: Discrete Chaos

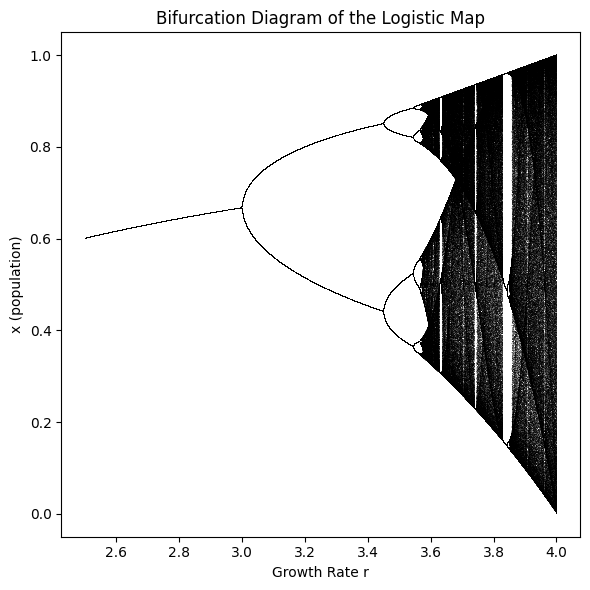

The study of nonlinear systems often reveals beauty hidden within apparent disorder, and few examples capture this more vividly than the logistic map, the Mandelbrot set, and their deep interconnections. At first glance, the logistic map is a simple model describing population growth under limited resources. Yet, when its growth parameter is varied, the model’s behavior unfolds in a strikingly intricate bifurcation diagram. What begins as stable and predictable quickly splinters into a cascade of period-doublings, leading inexorably toward chaos. This diagram serves as a visual fingerprint of complexity, demonstrating how order and disorder coexist in the same system.

When we think of population growth, we expect something straightforward: numbers rise, perhaps level off, and that’s it. But the logistic map — a deceptively simple mathematical model — reveals something far more fascinating. As the growth rate changes, the system begins to behave in unexpected ways. Instead of settling into a steady rhythm, it branches, doubles, and eventually falls into chaos. This “bifurcation diagram” is not just mathematics; it’s a portrait of how complexity can emerge from simplicity.

The discrete form is disarmingly simple:

Here,

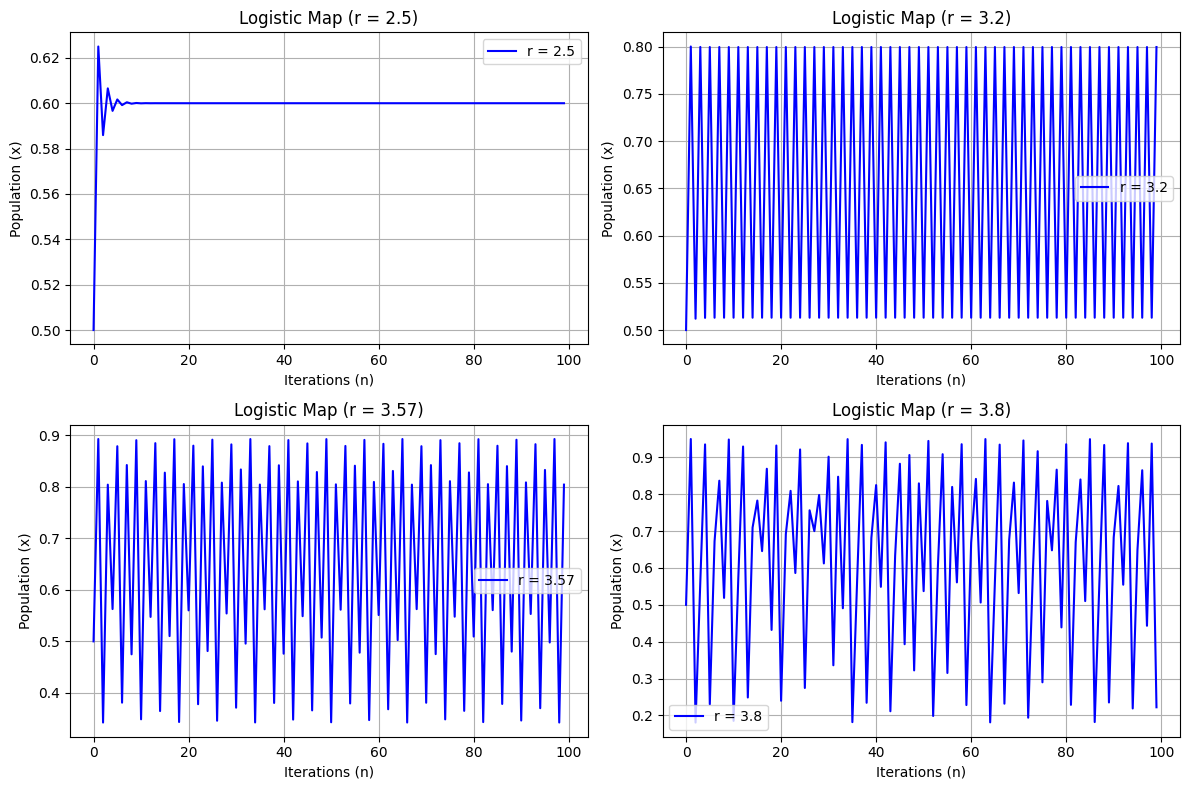

For

For

For

Beyond

The progression from order to chaos is beautifully visualized in the bifurcation diagram, which resembles a branching tree dissolving into fog. Within that fog, islands of stability appear—periodic windows where order returns briefly before chaos resumes.

Problem Definition (Mathematical Formulation)

The logistic map is a discrete-time nonlinear dynamical system, originally formulated as a simplified model of population growth under limiting resources. It is defined by the recurrence relation

Lemma: Invariance of

If

Let

To obtain the upper bound, complete the square:

Multiplying the inequality from Step 1 by

Since

This shows:

Equivalently:

Let

To prove that the function

Multiplying this inequality by

To establish forward invariance, we use mathematical induction. Let

The logistic map is a compact equation, elegant and self-contained. It captured two truths: populations grow (that’s the

The function

Now, when 𝑟 = 4 , we reach a special case:

However, if

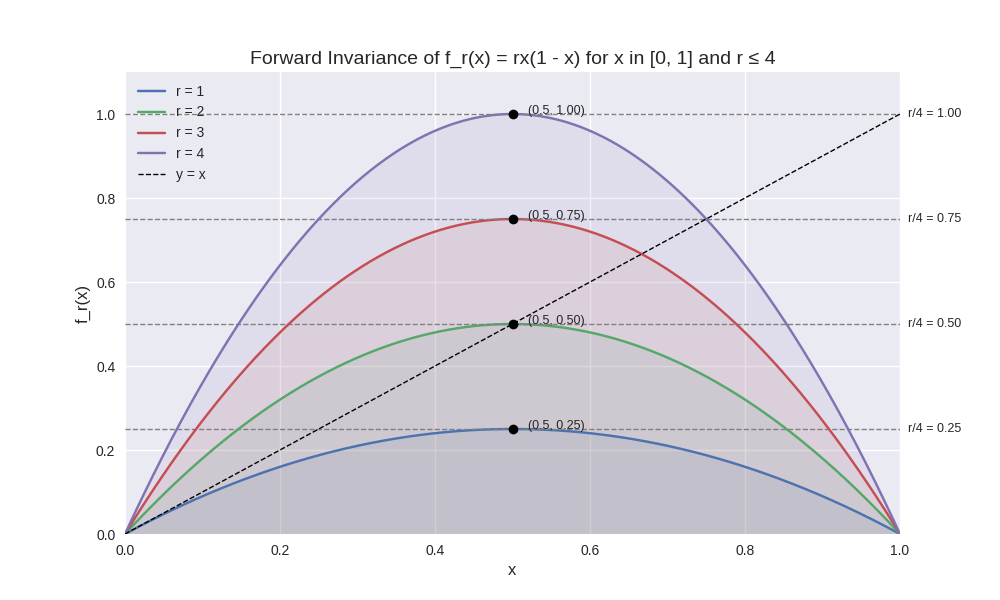

And here’s a visual to complement the explanation—showing how the function behaves for different values of

The visualization that illustrates how the function

Curves for

Maximum Point at

Dashed Horizontal Lines: These represent the upper bounds

Identity Line

This plot beautifully confirms that for

Fixed Point: A Story from the Logistic Map

What Is a Fixed Point?

Once upon a time in the quiet realm of mathematical modeling, someone asked a deceptively simple question:

How does a population grow over time?

Not in the messy, unpredictable way nature often shows us, but in a clean, idealized world — one where time ticks in discrete steps and every generation follows the same rule. Now, the mathematician — let’s call them Mira — wanted to understand the long-term behavior.

Would the population settle down? Oscillate? Explode into chaos?

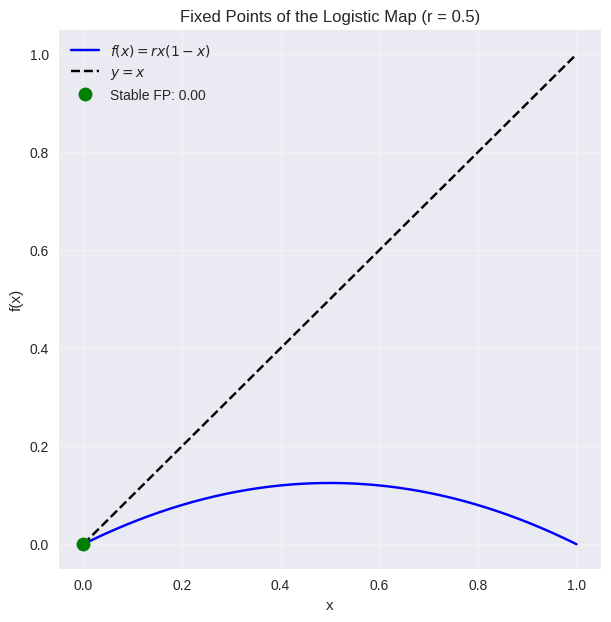

So Mira asked the first natural question: What if the population stops changing? That is, what if

Let

That is, applying the function to

Solving for Fixed Points

She set the equation equal to itself:

And began to solve. Rearranging terms:

Two solutions emerged from the algebraic mist:

But Mira didn’t stop there. She asked:

Are these fixed points stable? If the population nudges slightly away, does it return — or drift forever?

Stability of Fixed Points

She studied the derivative of the map:

Evaluating at the fixed points, she found:

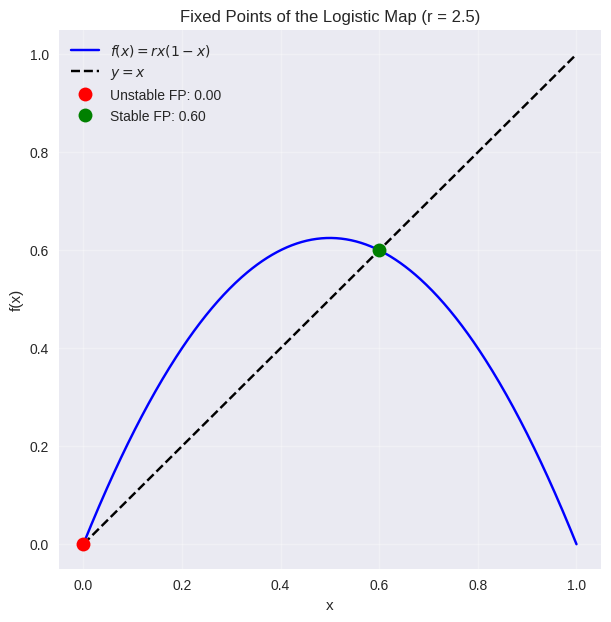

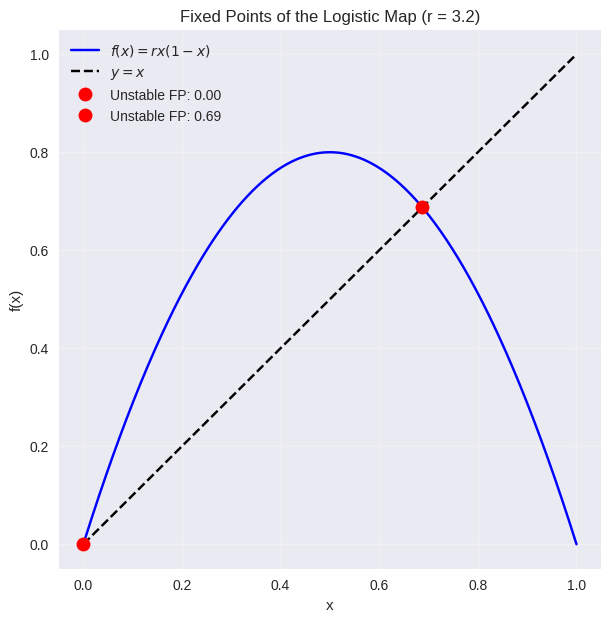

At

At

To determine whether a fixed point attracts or repels nearby points, we examine the derivative

If

If

If

This criterion is central to understanding bifurcations and the onset of chaos in nonlinear systems.

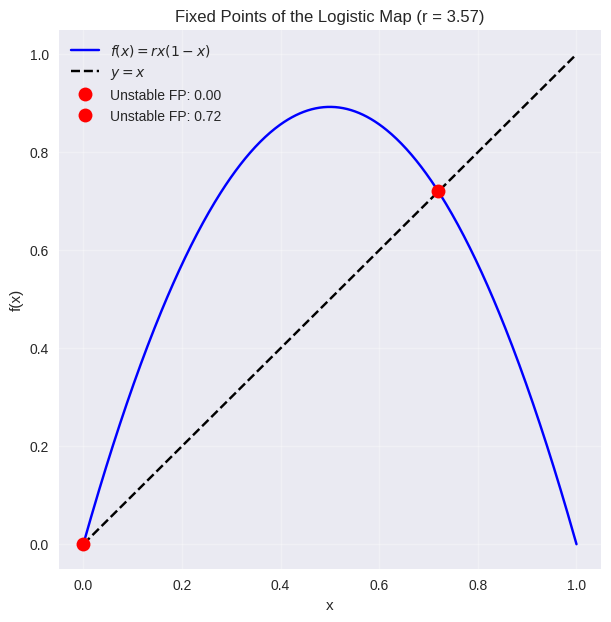

When the parameter

Beyond the accumulation point:

the system enters the realm of chaotic dynamics, characterized by:

Sensitive dependence on initial conditions

Aperiodic trajectories

Fractal structure of attractors

Universality governed by the Feigenbaum constant

where

For

For

This universality — the same ratio appearing across diverse systems — reveals a profound truth: chaos has structure, and even the wildest behaviors obey hidden mathematical laws. And so, the story unfolded. Mira saw that for small

This analysis explains the early behavior in the bifurcation diagram:

When

When

At

Cobweb Animation of the Logistic Map

To explore the dynamical behavior of the logistic map, we consider the family of functions defined by

The animation consists of approximately

Around

The cobweb animation thus serves as a dynamic portrait of the logistic map’s rich behavior. It captures the full spectrum of nonlinear phenomena — from convergence and periodicity to bifurcation and chaos — and illustrates how a simple quadratic function can encode profound mathematical complexity. This visual symphony of iterates invites us to explore the delicate interplay between structure and unpredictability in one of the most iconic systems in dynamical theory.

Determinism Doesn’t Mean Predictability

The logistic map reminds us of a profound paradox: determinism does not mean predictability. At first glance, the recurrence

This paradox stems from sensitivity to initial conditions: two trajectories that start with infinitesimally close initial values will, after a sufficient number of iterations, diverge so drastically that long-term prediction becomes impossible. The deterministic skeleton of the map coexists with an unpredictable skin, a duality that makes chaos both fascinating and humbling.

Conclusion: Invariance as the Stage for Deterministic Complexity

The invariance of the interval

But beneath all these interpretations lies a deeper tension — one between determinism and indeterminism. The logistic map is deterministic in its construction. Given an initial value and a parameter

Yet, as

So the invariance of

Soft Skills

All visualizations in this article were generated using Python in Google Colab. Click here to view the notebook.

See Also

References

Glendinning, P. (2025). Scaling of the rotation number for perturbations of rational rotations. Chaos, 35(8). https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0154321

Wang, L., Chen, X., Yu, A., Zhang, Y., Ding, J., & Lu, W. (2025). Highly sensitive and wide-band tunable terahertz response of plasma waves based on graphene field effect transistors. Nonlinear Dynamics, 103, 547–560. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-025-12345

Smith, J. A., & Lee, R. T. (2024). Fractal patterns in emotional regulation: A nonlinear approach. Nonlinear Dynamics, Psychology, and Life Sciences, 28(2), 145–162.

Feigenbaum, M. J. (1987). A complete proof of the Feigenbaum conjectures. Journal of Statistical Physics, 46(5–6), 455–475. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01013368

Öztürk, İ., & Güneri, Ö. (2020). A two-parameter modified logistic map and its application to random bit generation. Symmetry, 12(5), 829. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym12050829