Intellectual fascination crosses many boundaries. Here, Paradoxes lead us to define and push our intellectual boundaries which comes from our intellectual fascination.

Distinct from Our Opinion

There is a dilemma i.e., you have three envelopes and you can choose only one. They are red, white and brown.

‘Di’ comes from the Greek for ‘twice’ and ‘lemma’ means ‘premise’. So, a dilemma involves two premises from which you have to choose. Adding a third envelope means this isn’t technically a dilemma. But it does set up a very famous paradox.

Let’s dissect the word paradox like we just did with a dilemma to find out what a paradox is.‘Para’ comes from the Latin ‘distinct from’ and ‘dox’ comes from ‘doxa’, meaning “our opinion”. Paradox translates literally as “distinct from our opinion”.

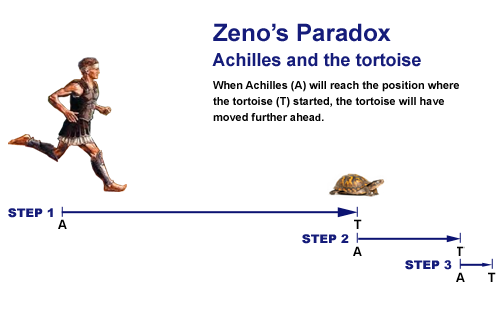

Can Mathematics Conquer Achilles?

Zeno knew Achilles could catch up to the tortoise in real life, but couldn’t prove it mathematically. He thought there would be an infinite number of new points for the tortoise to reach that Achilles had to reach because he didn’t know that an infinite series of numbers could add up to a finite value. No one knew that for another 2000 years. Now we call a convergent series,

This infinite series goes on forever, but it eventually adds up to 1. And at that 1 is where, mathematically, Achilles finally reaches the tortoise. We knew that Achilles could catch up to the tortoise, but it took inventing calculus for us to prove why. This is why this paradox that confounded great minds for thousands of years is falsidical. Described by Willard Van Orman Quine like this,

A falsidical paradox packs a surprise, but it is seen as a false alarm when we solve the underlying fallacy

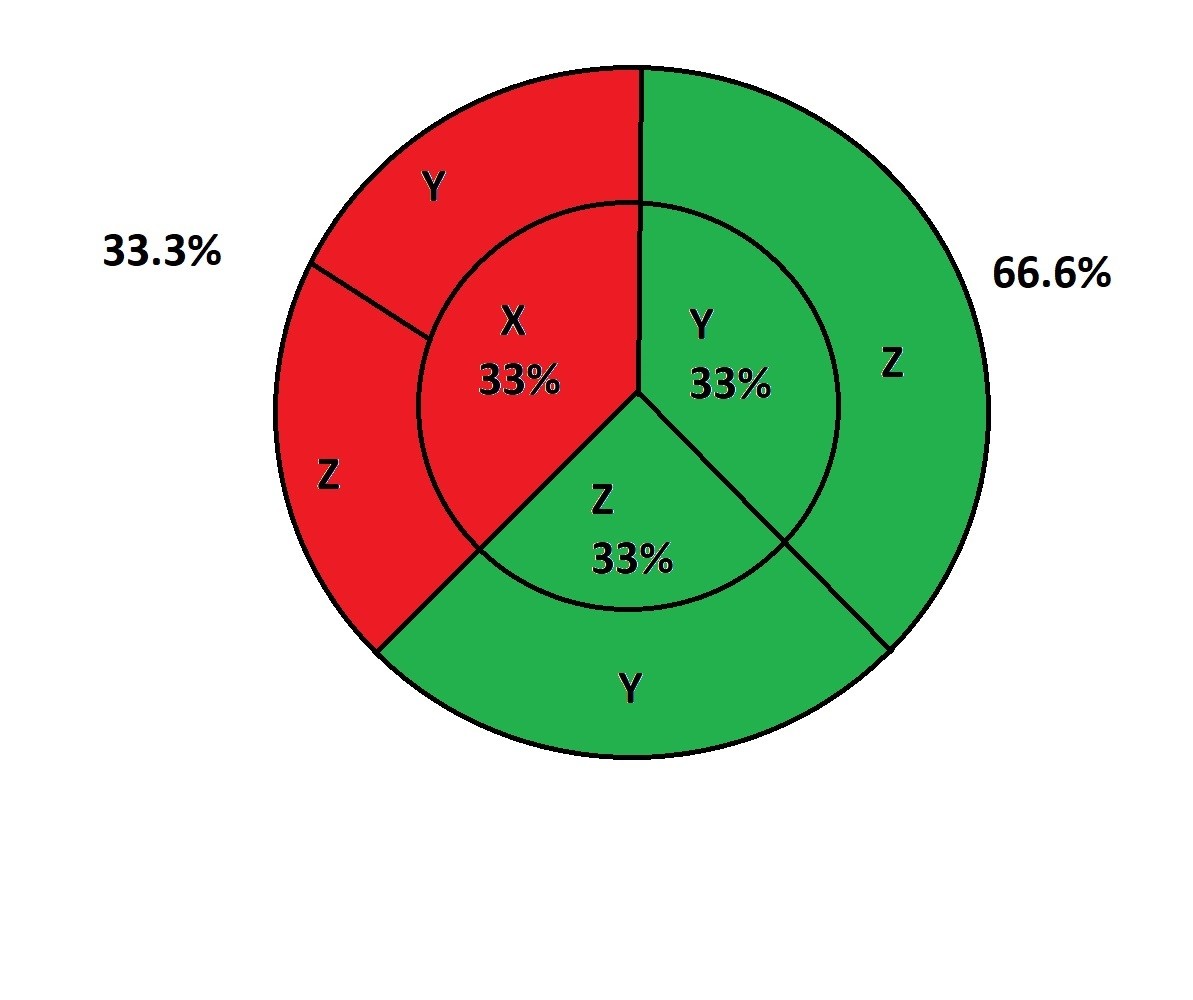

So, one paradox envelope down, and two go to go. Again, assume that behind the envelope white we have: Veridical. To understand this if we conduct a game show like this if we replace the two envelopes you’ve already opened with some prizes. How about we put a million dollars into one of them and Sherlock Holmes (Sherlock Holmes is a fictional detective created by British author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle) in the other? The third and brown envelope still contains the term for the final type of paradox. There is a second person who is hosting the game show he/she writes 1,2,3 according to his/her preference, host shuffles these up and he/she asks you to choose the correct one and you’ll win the grand prize. After you make your selection (without switching the envelope), let’s say envelope X. The game show host reveals what’s inside one of the two remaining envelopes. It’s Sherlock Holmes. Now there are only two envelopes left: The one that you’ve chosen and the remaining mystery envelope. He gives you the option to switch your envelope.

Should you do it? Does it even matter?

From this point of view, your odds of winning clearly 50/50. You should always switch. And here’s why. The odds of winning with your first chosen envelope are 1/3. So, you have a 33.33% repeating chance of being right and a 66.66% repeating chance of being wrong. When the game show host revealed the Sherlock, it didn’t suddenly improve your odds to 50/50. The proof is in the options. After first choosing an envelope, the thing revealed by the host will never be the money because that would ruin the tension of the game show. So, if your initial 1 out of 3 picks wasn’t the money and the money is Y, then the host will reveal Z. If you chose wrong and the money is Z, then the host reveals Y. If you luckily chose the money the first time, then the host can reveal either Z or Y. It doesn’t matter. No matter what you’re still stuck in that initial 33% chance that you chose right the very first time. If you switch, regardless of the prize revealed, you now leap into the 66% zone. You’ve doubled your chances of getting the money.

To put it another way, when you are asked if you want to switch, you’re actually being given a dilemma: Do you want to keep your single envelope, or do you want both of the other two? It just so happens that you already know what’s inside one of them. But since the one revealed will never contain the money, the chances that the other unopened envelope has the money are twice as high as the first one that you chose.

The Monty Hall Problem blew up after a 1990 Parade magazinecolumnist advocated switching doors in this same scenario from the game show “Let’s make a deal”. When she told readers they should always switch to improve their odds of winning nearly about 1,000 people with PhDs wrote in to tell her that she was wrong. They were. So, the ‘Monty Hall Paradox’ is like the Potato Paradoxis an example of one that is a ‘Veridical Paradox’, one that initially seems wrong, but is proven to be true.

A veridical paradox packs surprise, but the surprise quickly dissipates itself as we ponder the proof.

— Willard Van Orman Quine

There are paradoxes that seem absurd but have a perfectly good explanation, and ones that seem false and actually are false because of an underlying fallacy even if it takes a major advance in mathematics to prove it.

The remaining last envelope, the 3rd envelope contains the kind you think of when you think of paradoxes i.e., Antinomy. The Grandfather Paradox is where you go back in time to kill your grandfather when he was a child but that means your father was never born so you weren’t born. So, how could you go back in time to kill your grandfather? It’s ridiculous. MinutePhysicsproposed a solution to this but these types of paradoxes are not true or false. Actually, they can’t be true and they can’t be false. As Willard Van Orman Quine put it, they create a crisis “Crisis in thought”.

I am Lying

If I’m lying when I say that, then I must actually be telling the truth. But how can I be telling if I’m lying? The Liar Paradox is an example of Antinomy which literally means ‘Against law’ & highlights a serious logical incompatibility.

An antinomy packs a surprise that can be accommodate by nothing less than a repudiation of part of our conceptual heritage. — Willard Van Orman Quine

Antinomies are paradoxes to us all. Falsidical and veridical paradoxes are only paradoxes to those who don’t know the solution, but they are still of value. Every time we resolve a scenario that runs counter to our or someone else’s initial expectations, every time we learn the how and why and share that information. We’re refining and clarifying knowledge. Which makes all three types of paradoxes excellent tools for reasoning. Whether or not something is paradoxical to an individual depends on the accuracy of their expectations. Today, modern mathematics has given us the ability to show that Zeno’s paradoxes are falsidical. But they were pure antinomy, unresolved to everyone for millennia.

One man’s antinomy is another man’s falsidical paradox, give or take a couple of thousand years.

— Willard Van Orman Quine

Who knows which antinomies of today will be solved in the future? Right now we are struggling with the paradox of the Faint Young Sun: our current knowledge of stars says that billions of years ago, our sun wasn’t hot enough to keep the Earth from being a ball of ice. But our geological evidence shows an ancient Earth with liquid oceans and budding life when everything should have been frozen. How could the Earth have liquid water without a sun hot enough to melt ice? It’s antinomy until we fully comprehend the situation. Maybe our current understanding of the sun isn’t perfect or maybe our knowledge of early Earth is missing some pieces.

A paradox is a problem where the solution is, or made to seem, impossible. Sometimes they’re purposely designed for fun because our minds like puzzles. Sometimes we just stumble on a gap between what we know and how we talk about what we know, and what is actually true. When we solve an impossible antinomy, it becomes falsidical or veridical. Someone who knows the answer can see what the problem was all along: We tricked ourselves by knowing too little or by asking the wrong question. In one way or another, all paradoxes come from people. By challenging us to find the flaw or fill the gap in our knowledge, paradoxes help us to define and push our intellectual boundaries. There’s always for us to know. Whether we know it or not.

References:

Ontological relativity Book by Willard Van Orman Quine.

The Paradox of Choice Book by Barry Schwartz.

The Pea and the Sun A Mathematical Paradox by Leonard M. Wapner.

Mathematical Fallacies and Paradoxes by Bryan Bunch.

What the Tortoise Said to Achilles by Lewis Carroll.