Unpacking Laurent Expansions in Complex Analysis

A Deep Exploration of Analytic Structure, Principal Parts, and Convergence Domains

Introduction

In complex analysis, one of the most powerful tools for understanding functions near singularities is the Laurent series. While the Taylor series expresses a function as an infinite sum of non-negative powers of

The concept was introduced in 1843 by the French mathematician Pierre Alphonse Laurent, who showed that many complex functions that cannot be represented by a Taylor expansion (because of singularities) can still be expressed as a convergent series if negative powers are included. In this way, the Laurent series generalized Taylor’s idea, opening the door to the modern theory of residues and singularities. Generally, if a function

then it can be expressed as,

where the terms with

It naturally describes functions around isolated singularities.

The coefficient

It provides a systematic way to classify singularities as removable, poles, or essential.

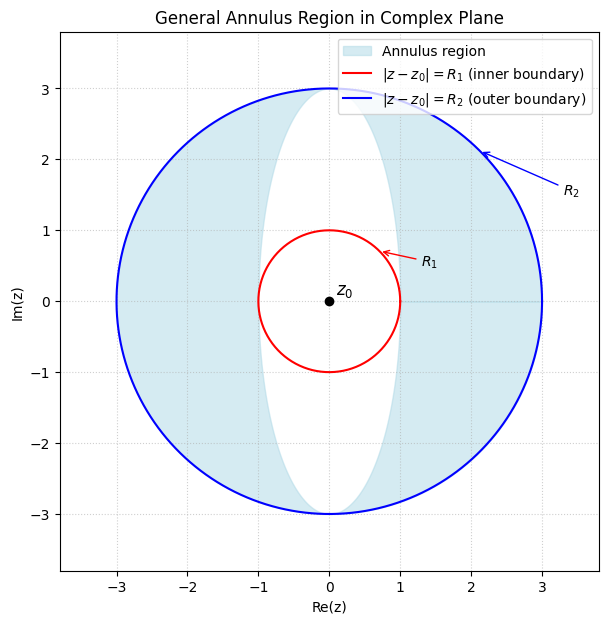

An annulus in the complex plane is the open region between two concentric circles centered at some point

Formally, for

Intuition

If

If

Otherwise, it’s a “ring-shaped” region that excludes the inner circle

In this article, we adopt a problem-solving perspective on the Laurent series. We begin with its foundational definition, proceed to examine expansions around various points in the complex plane, and systematically work through illustrative examples.

The Laurent series converges precisely in an annulus.

The inner radius

The outer radius

So, the annulus captures exactly the region where the series is valid.

Here’s the geometric illustration of a general annulus in the complex plane:

- The center is at

- The inner boundary is the circle

- The outer boundary is the circle

- The shaded ring-shaped region between them is the annulus:

This is exactly the domain where a Laurent series converges.

By the conclusion, readers will not only master the techniques for computing Laurent series, but also begin to see how these expansions act like X-rays—revealing hidden singularities, symmetries, and the layered anatomy of complex functions that ordinary power series leave untouched.

For readers who wish to explore the concept of an analytic function not only from its theoretical definition but also through rich visual and computational perspectives, please refer to my GitHub repository.

Definition (Laurent Series)

Let

where

So we are adding up contributions from all integer values of

The coefficients

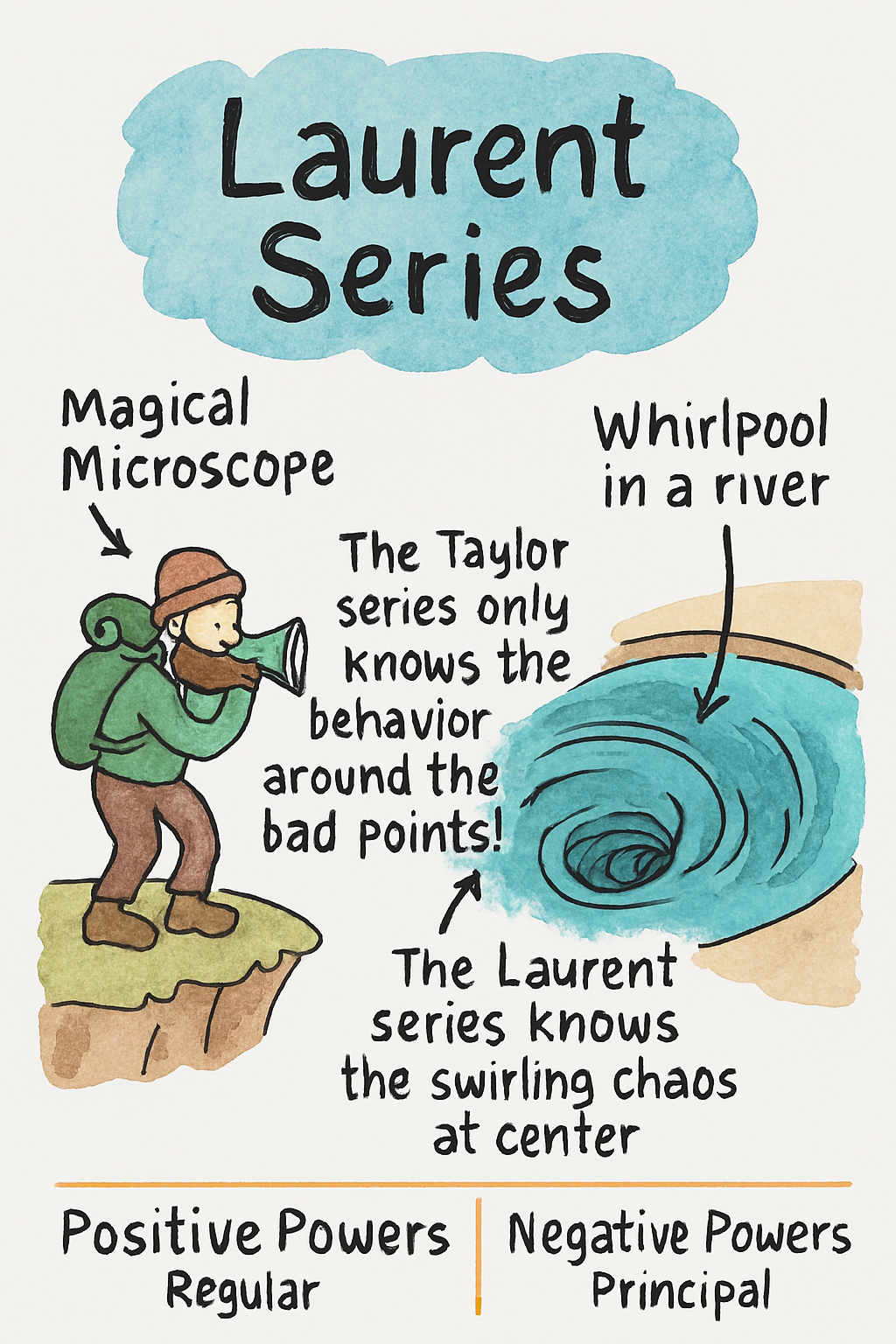

This sketch offers a poetic visualization of the Laurent series, casting it as a “magical microscope” that reveals the hidden dynamics of complex functions near singularities. On the left, we see a hiker—symbolizing the curious mathematician—standing at the edge of a river, peering through a microscope toward a swirling whirlpool. This whirlpool represents a singularity, a point where the function misbehaves and the Taylor series fails to describe it.

The Laurent series, however, doesn’t shy away from this chaos—it embraces it. By including both positive and negative powers of

So, Laurent series is just a generalization of Taylor series that allows negative powers, making it suitable to represent functions near singularities.

Explanation of the Definition

- Domain of validity: Unlike Taylor series (which converges only inside a disk), Laurent series is valid in an annulus

If

If

- Two parts of Laurent series:

Analytic part:

Principal part:

- Utility:

Laurent series is essential for classifying singularities (removable, pole, essential).

Residue theorem uses the coefficient

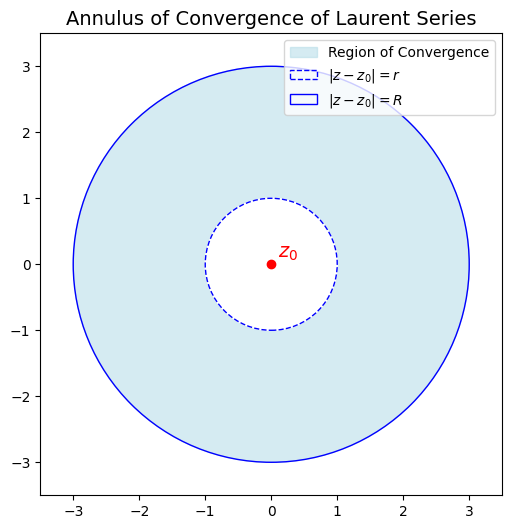

To deepen the intuition behind the Laurent series, it helps to visualize the geometry of its domain—specifically, the annulus. Imagine a donut-shaped region in the complex plane, centered around a singularity. This annulus lies between two concentric circles: the inner boundary excludes the singularity, while the outer boundary marks the limit of convergence. Within this ring, the Laurent series converges beautifully, weaving together both positive and negative powers of

Here’s the geometric intuition for a Laurent series expansion:

- The red dot is the expansion point

- The dashed inner circle (

- The solid outer circle (

- The blue shaded annulus is the region where the Laurent series converges.

So, unlike a Taylor series (which converges only in a disk), a Laurent series converges in a ring-shaped domain.

The Rigorous Criterion

Let

Let

be the distance from

Let

be the distance from

which converges for

and the resulting power series converges for that annulus (standard proofs use uniform convergence of the geometric series expansions and Cauchy estimates).

Theorem (Annulus of convergence for a Laurent expansion)

Statement.

Let

Define

with the convention that an infimum over an empty set is

which converges for every

Moreover the coefficients are given (for any

Problem Solving

Example Problems

Example 1: Simple Rational Function

Expand the function

into a Laurent series about (

Case (a): (

We begin by rewriting the function:

To expand

Substituting back into

Explicitly, this becomes:

This is a Laurent series with a principal part term

(b) Region: (

In this region, we manipulate the function differently:

We rewrite

So the Laurent series becomes:

Explicitly:

Here, there is no principal part beyond

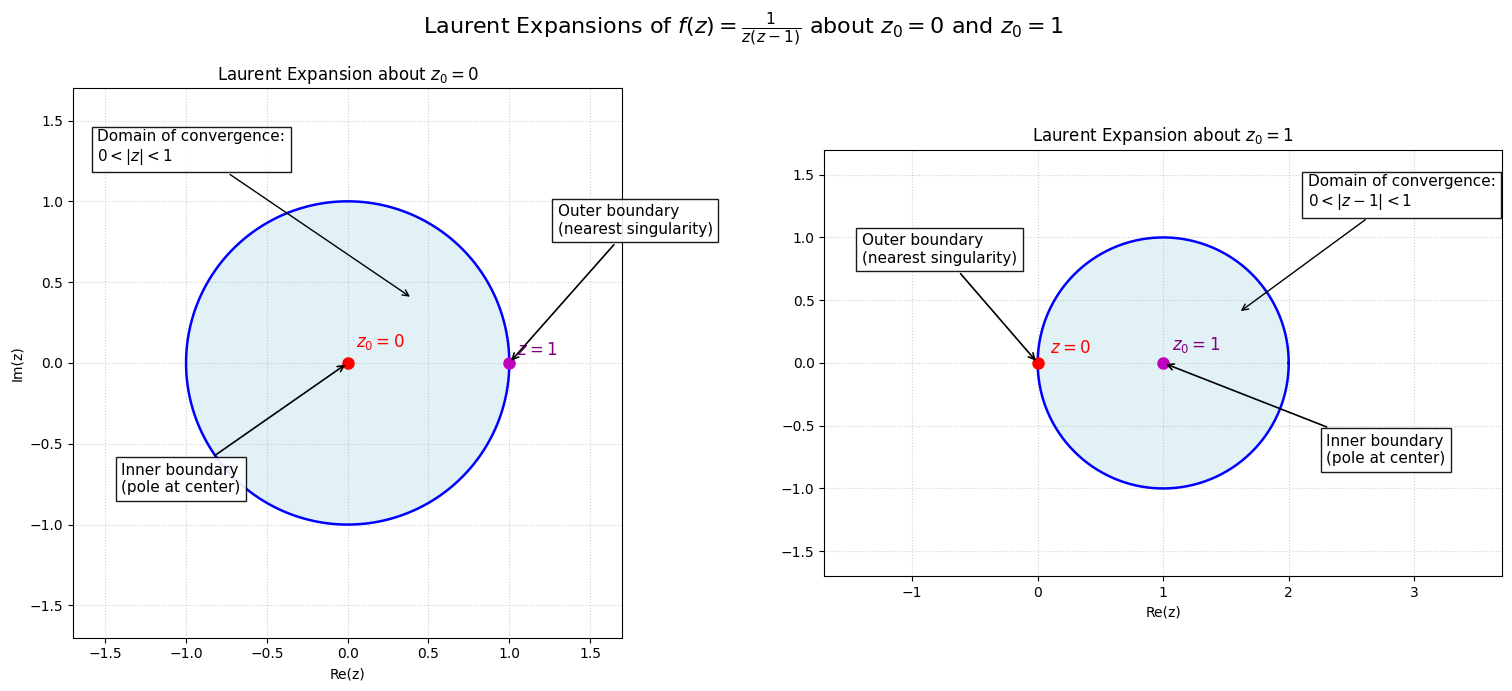

I marked the two expansions of

Region

Laurent expansion (centered at

Principal part (negative powers) — boxed on the lower-left of that diagram:

Analytic part (Taylor-like, non-negative powers) — boxed on the upper-right of the diagram:

Interpretation: there is one simple pole at

How we got it quickly:

Region

Laurent expansion (right diagram):

Here there is no analytic (nonnegative-power) part about

Interpretation: for

For this exploration, we will focus on rigorously computing the structure and behavior of the annulus by delving into the full mathematical details. Rather than relying solely on visual intuition or heuristic descriptions, our aim is to analytically characterize the annular region—its boundaries, the nature of singularities within it, and the corresponding Laurent expansions. This approach will involve precise definitions, careful residue computations at key singular points, and a step-by-step breakdown of how each term in the expansion reflects the geometry and analytic structure of the domain. By grounding our analysis in formal mathematics, we not only clarify the underlying theory but also build a robust foundation for deeper insights into complex function behavior on multiply-connected domains.

Rigorous Computation for

1. Locate the singularities.

The function is rational; its singularities are the zeros of the denominator:

(There is also a singularity at infinity which matters only for exterior expansions.)

2. Domain of analyticity around

The function is analytic on

Thus there are two maximal annular regions centered at

the punctured disk (inner annulus)

the exterior annulus

A Laurent series about

3. Compute the expansions and their radius of convergence.

Inside

where we used the geometric series

The geometric series converges iff

Outside

Hence

This is a Laurent expansion in negative powers of

Conclusion for

If you ask for the Laurent series that represents

In complex analysis, a residue is one of the most important quantities associated with a function near a singularity. When a function becomes unbounded or undefined at a point—called a singularity—the residue extracts the essential numerical information that describes the function’s behavior in the immediate neighborhood of that point.

Compute residues at the simple poles

At

At

You can see

For further theoretical development and conceptual clarification, follow my GitHub repository

Conclusion

The Laurent series provides a unified framework for understanding the local behavior of complex functions around singularities. Unlike the Taylor series—which applies only to holomorphic functions—the Laurent expansion naturally accommodates poles and essential singularities by separating the expression into two fundamental components:

the principal part, consisting of negative powers, which encodes the singular behavior and isolates the obstruction to analyticity; and

the analytic part, which behaves identically to a Taylor series and captures the regular, holomorphic contribution.

For a fixed center

Ultimately, the Laurent expansion not only extends Taylor’s idea but also lies at the heart of the Residue Theorem, enabling the computation of otherwise intractable contour integrals through the extraction of a single coefficient—the residue. This synthesis of geometric intuition, analytic decomposition, and algebraic structure forms one of the most elegant and useful results in complex analysis.

Readers interested in practicing these concepts are encouraged to attempt the accompanying problem set.

Soft Skills

All visualizations in this article were generated using Python in Google Colab. Click hereto view the notebook.

References

Busam, R. and Freitag, E., 2009. Complex analysis. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

Ablowitz, M. J., & Fokas, A. S. (2021). Introduction to Complex Variables and Applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.